Chris Tilling has posted the following quote from Ernst Kasemann:

‘Every simplification which forces the original variety of voices [of the biblical texts] into a well trodden path, is sin against the Spirit’!

—(from his essay “Justification and salvation-history in Romans”

Kasemann in Pauline Perspectives – Tilling’s translation from the German original, p. 118)

One thing I have learned from my graduate work in biblical studies is that we too often blur and downplay the Biblical message by merging and harmonizing passages which should rather be read distinctly. Often those of us who believe that the Bible is divinely inspired so quickly want to mute tensions within the Bible, including those created by the unique voices and perspectives of its authors. However, it seems to me that any belief that God spoke and speaks through biblical texts would also mean that the these authorial voices and perspectives, even in areas where they may differ, are inherently important in revealing God’s message to us.

Example 1: Paul and James

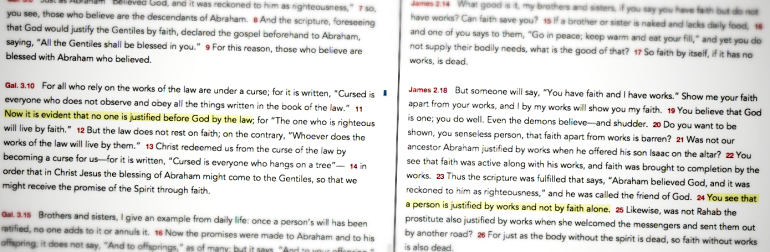

I don’t know how anyone reading Paul’s Letter to the Galatians and the Epistle of James can think that those two authors saw things eye-to-eye or presented them that way. The segments regarding “faith and works” in these letters feels as if one of them is responding rhetorically to the other—and, again, they don’t seem to be in agreement. These differences have been noted (even when apologetically downplayed) by several Christian authors and translators throughout Church history.. [1]

One can imagine the following conversation (emphasis added from my imagined face-to-face debate between the two of them):

Note in particular Paul’s opening statement and James’ last sentence. Maybe Paul and James disagree, or maybe they are just using language differently or their starting points are different, but there are differences in their presentations. Note also James’ use of the word “barren,” which could also be a contrast between Paul’s later use in Galatians of the idea of “fruit.”

Example 2: Shepherds and Wise Men

Another example of contrasts in the individual voices of biblical authors would be the birth stories of Matthew (Matt 1:18-2:23) and Luke (Luke 1:26-56; 2:1-40). These are stories so familiar to most Christians that we tend to automatically merge and harmonize them into one single story. Unfortunately, in doing so we may miss the unique message each Gospel writer meant to communicate to us. A few years ago, I divided students into groups to read the birth narratives from the gospels of Matthew and Luke. Each group would read from only one gospel, without taking notes, and then verbally summarize what they had read. After their first read, the “Matthew Group” of students recounted their version. When I told them that they incorrectly mentioned shepherds in the story and that Matthew never mentions shepherds, the students argued (somewhat angrily) with me that they had “just read about shepherds in Matthew!” The “Luke Group” did the same concerning the “Wise Men.”Due to familiarity, even when reading directly from the text, they harmonized unique stories into one single version. It wasn’t until they were directed to read their passage again, looking for these specific elements, that they recognized they had added them.

Later, I shared this interesting occurrence with another faculty member, a person who reads scripture regularly. She then asked: “The birth stories are different?” Despite her many years of reading these stories, she had not considered their differences: shepherds and wise men, Mary and Joseph, angels and dreams, Jerusalem and Egypt, Bethlehem and Nazareth, etc.

Embracing the God-Breathed Differences

My thoughts are this: What if attempting to minimize and/or do away with the differences in the unique voices within biblical texts we are actually missing something the Spirit of God is trying to say? Despite popular statements proclaiming the Bible’s “simple message”, this ancient collection of texts is complex—as one should probably expect of the revelation of God, truth, and life. I don’t think our fear of “contradictions” in the Bible should cause us to approach the text dishonestly or in an over-simplifying (simplistic) manner which attempts to minimize or do away with entirely the tensions which make us uncomfortable. Personally, I find that when I allow the uniquely human voices within the Bible speak, even though it often complicates matters and leaves me with more questions than answers, the God-breathed mystery of it all draws me even more deeply into the text.

Who knows, maybe one of the key messages God intends for us is that the unity of those who follow Christ is more about being found united in Christ rather than how much we agree and that we can graciously pursue Him and his Kingdom together despite our differences.

NOTES

[1] Luther, for example, wrote:

Though this epistle of St. James was rejected by the ancients, I praise it and consider it a good book, because it sets up no doctrines of men but vigorously promulgates the law of God. However, to state my own opinion about it, though without prejudice to anyone, I do not regard it as the writing of an apostle; and my reasons follow.

In the first place it is flatly against St. Paul and all the rest of Scripture in ascribing justification to works. It says that Abraham was justified by his works when he offered his son Isaac; though in Romans 4 St. Paul teaches to the contrary that Abraham was justified apart from works, by his faith alone, before he had offered his son, and prove it by Moses in Genesis 15. Now although this epistle might be helped and an interpretation devised for this justification by works, it cannot be defended in its application to works of Moses’ statement in Genesis 15. For Moses is speaking here only of Abraham’s faith, and not of his works, as St. Paul demonstrates in Romans 4. This fault therefore, proves that this epistle is not the work of any apostle.

In the second place its purpose is to teach Christians, but in all this long teaching it does not once mention the Passion, the resurrection, or the Spirit of Christ. He names Christ several times; however he teaches nothing about him, but only speaks of general faith in God. Now i is the office of a true apostle to preach of the Passion and resurrection and office of Christ, and to lay the foundation for faith in him, as Christ himself says in John 15 “You shall bear witness to me.” All the genuine sacred books agree in this, that all of them preach and inculcate [treiben] Christ. And that is the true test by which to judge all books, when we see whether or not they inculcate Christ. For all the Scriptures show us Christ, Romans 3; and St. Paul will know nothing but Christ, I Corinthians 2. Whatever does not teach Christ is not apostolic, even though St. Peter or St. Paul does the teaching. Again, whatever preaches Christ would be apostolic, even if Judas, Annas, Pilate, and Herod were doing it.

But this James does nothing more than drive to the law and to its works. Besides, he throws things together so chaotically that it seems to me he must have been some good, pious man, who took a few sayings from the disciples of the apostles and thus tossed them off on paper. Or it ma perhaps have been written by someone on the basis of his preaching. He calls the law a “law of liberty,” though Paul calls it a law of slavery, of wrath, of death, and of sin.

Moreover he cites the sayings of St. Peter: “Love covers a multitude of sins,” and again, “Humble yourselves under the hand of God;” also the saying of St. Paul in Galatians 5, “The Spirit lusteth against envy.” And yet, in point of time, St. James was put to death by Herod in Jerusalem, before St. Peter. So it seems that this author came long after St. Peter and St. Paul.

In a word, he wanted to guard against those who relied on faith without works, but was unequal to the task in spirit, thought, and words. He mangles the Scriptures and thereby opposes Paul and all Scripture. He tries to accomplish by harping on the law what the apostles accomplish by stimulating people to love. Therefore, I will not have him in my Bible to be numbered among the true chief books, though I would not thereby prevent anyone from including or extolling him as he pleases, for there are otherwise many good sayings in him. One man is no man in worldly things; how, then, should this single man alone avail against Paul and all the rest of Scripture?

—Luther’s Works, vol 35 (St. Louis: Concordia, 1963), pp. 395-396

Gal 2 v Jm 2- Tension…NOT!

“Works of the law” are clearly distinguishable from “Works of faith”. This is where we begin to resolve the “existent” tension; if there be any at all. All points being equal the question is begged, “does the context even allow such a thing as ‘tension’ concerning these texts- together?” One is clearly concerning a means to an end whilst the other the meaning of an end. One looks to the cross and the other back at it. One vindicates the other validates.