When debating the Constitutional amendments that would eventually become the Bill of Rights, Patrick Henry advocated strongly for an amendment providing for protections against the use of “excessive bail and fines” and “cruel and unusual punishment.” His case was this: While our governing representatives could be allowed latitude to write laws defining crimes and enforcing punishment, they could not be trusted with the same (or any) latitude when it came to ensuring limits to punitive actions. He stated: “But when we come to punishments, no latitude ought to be left, nor dependence put on the virtue of representatives.”

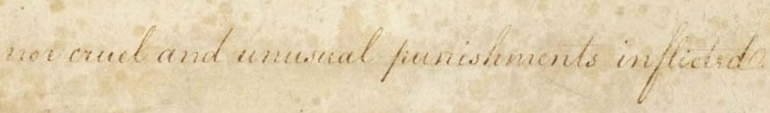

Arguing that these protections were heavily due to the heritage of English common law, Henry rhetorically noted: “What has distinguished our ancestors? That they would not admit of tortures, or cruel and barbarous punishment.” He felt strongly that this heritage must be preserved as written law within the Constitution of our own system of government. Noting the recently written Virginia Declaration of Rights had already guaranteed such protections (“that excessive bail ought not to be required, nor excessive fines imposed, nor cruel and unusual punishments inflicted”), Henry asked those his fellow Virginians who opposed him: “Are you not, therefore, now calling on those gentlemen who are to compose Congress, to . . . define punishments without this control?”

Henry was certain that without an amendment providing protection against “cruel and unusual punishment” our government would inevitably fall into the practices of other nations, which allowed for not only cruelty and torture as a form of punishment, but as means of coercing confessions:

“But [without an amendment prohibiting cruel and unusual punishment…] they may introduce the practice of France, Spain, and Germany: of torturing, to extort a confession of the crime . . . and they will tell you that there is such a necessity of strengthening the arm of government, that they must have a criminal equity, and extort confession by torture, in order to punish with still more relentless severity. We are then lost and undone.”

It is notable that Henry clearly understood the reasons and reasoning which would ultimately be given for such behavior: “They [the government representatives] will tell you there is … necessity of strengthening the arm of government, that they must have criminal equity…” (emphasis added). The notion of “criminal equity” is something like, “Rather than be limited by the rule of law, we must have freedom and latitude to punish and coerce criminals however we see fit according to the circumstances.” Or, perhaps more clearly, it is a way for government to say, “Trust us to do what’s right when it comes to how we treat whoever we consider a criminal”—to which Henry’s answer was clear: never. Torture “cruel and barbarous.” Even allowing our government the latitude to consider such actions was a potential threat to the rights and freedoms guaranteed by the Constitution. Henry’s last statement is strong enough to warrant this conclusion. If we engage in these acts “. . . We are then lost and undone.”

Source Material

Document 13: Debate in Virginia Ratifying Convention

16 June 1788

Patrick Henry: “Congress, from their general powers, may fully go into business of human legislation. They may legislate, in criminal cases, from treason to the lowest offence [sic]—petty larceny. They may define crimes and prescribe punishments. In the definition of crimes, I trust they will be directed by what wise representatives ought to be governed by. But when we come to punishments, no latitude ought to be left, nor dependence put on the virtue of representatives. What says our [Virginia] bill of rights?—”that excessive bail ought not to be required, nor excessive fines imposed, nor cruel and unusual punishments inflicted.” Are you not, therefore, now calling on those gentlemen who are to compose Congress, to . . . define punishments without this control? Will they find sentiments there similar to this bill of rights? You let them loose; you do more–you depart from the genius of your country.

In this business of legislation, your members of Congress will loose the restriction of not imposing excessive fines, demanding excessive bail, and inflicting cruel and unusual punishments. These are prohibited by your declaration of rights. What has distinguished our ancestors?—That they would not admit of tortures, or cruel and barbarous punishment. But [without an amendment prohibiting cruel and unusual punishment] Congress may introduce the practice of the civil law, in preference to that of the common law. They may introduce the practice of France, Spain, and Germany–of torturing, to extort a confession of the crime. They will say that they might as well draw examples from those countries as from Great Britain, and they will tell you that there is such a necessity of strengthening the arm of government, that they must have a criminal equity, and extort confession by torture, in order to punish with still more relentless severity. We are then lost and undone.”

Elliot, Jonathan, ed. The Debates in the Several State Conventions on the Adoption of the Federal Constitution as Recommended by the General Convention at Philadelphia in 1787. 5 vols. 2d ed. 1888. Reprint. New York: Burt Franklin, n.d.

Material taken 3:447–48, 451–52 (http://press-pubs.uchicago.edu/founders/documents/amendVIIIs13.html)